© 2023 William Bowles

I know about exile. Cut adrift, divorced from your roots, cast aside, alienated, yet there is strength in numbers, thus we congregate: verb [no object] gather into a crowd or mass. But yet still cut adrift, thus a yearning takes place for that which is lost yet still remembered. Not being a Puerto Rican or even Nuyorican yet connected by history, by belonging, by distance, by being apart I feel a part of that crowd, that mass of humanity thrust into a corner of Manhattan Island by the simple movement of capital. Exiled by association. And therein lies a tale, of one exile to another.

Events led me to East Harlem, Spanish Harlem, Nueva York, the Upper East Side of Manhattan Island. Formerly the home of yet more exiles, then it was Italian, now it’s Spanglish. Then they merged, then the rhythms changed. Then the Island invaded. Was invaded. It was in East Harlem, El Barrio, that I met Nestor Otero, I think it was 1977, I’d been in Nuevayork for less than 2 years and through happenstance found myself as the designer for el Museo del Barrio, the Museum of the Neighbourhood, the first Hispanic museum in the US. How did it happen that myself, a Brit, of Russian-Jewish extraction from South London, found myself working in el Museo? It’s where I met Nestor, well actually, to be more precise it was at Taller Boricua, an arts centre populated by Puerto Ricans, some in exile, that was situated in the same neighbourhood, on Lexington and 105th Street that we first met and thus began a long association of work and friendship. We became companéros.

Oddly, or perhaps not, I felt at home in East Harlem, damn, I felt at home in Harlem! And although viewed with some suspicion, after all, I was this white, foreigner but weren’t we all foreigners? Aren’t all but the original inhabitants, foreigners? But I felt at home there, surrounded by foreigners, who spoke a different language, perhaps it was class that united us? But more of this later. The streets of East Harlem for example, though pulsing to a different beat, felt familiar to me. I loved walking across 106th Street, hearing the clack of dominoes or the congueros, the salsa pouring from open windows, the smell of cooking, the place was alive! Even the burnt out building plots where Nestor and I would hunt for found objects, bits of former apartments, to populate his artworks, it was after all, the 1970s and Fort Apache ruled.

So what was it about East Harlem, why did I feel so at home there? And Nestor, how could two people, coming from such different backgrounds, such different experiences find a commonality of interests. Nestor, Vietnam vet, who would never talk about his experiences there except to mention, once to me, his nightmares and what I perceived as his shame, which is probably why he didn’t want to talk about it. How could such a beautiful young man have been subjected to such horrors? What did he ever do to deserve such mistreatment? Well, he was Puerto Rican for a start and he was working class for a second.

Once, Nestor who was about to have his first one-person show, in Puerto Rico, asked me to write an essay for the catalogue, but why me, I asked? I felt inadequate to the task. Surely a Puerto Rican would be better placed? Nestor suggested that perhaps that should be the theme and looking back, he was right, it was about what united us, what we shared as human beings, why it was so important that connections were made. That’s what Nestor’s work was all about; connections. In turn, it explained why we could work together so well. So that became the theme of the essay and I find myself, repeating the process 40 years later! Well almost. But now it’s what’s changed in those intervening decades and what’s become of the theme: Colonialization and therein lies the connection.

Left, the Author, Right, Nestor. Photo by the artist, José Morales in his studio on 104th Street probably c. 1980

The New York of those days, heady days really, was a cauldron. Puerto Rico was ‘flavour of the month’ then, it was fashionable to be Puerto Rican, up to a point that is. The point being independence for Puerto Rico. And whilst Nestor’s work was never overtly political nor about independence per se, it was intrinsically political because it was all about being a Puerto Rican in New York. The island emerged like Atlantis rising from the ocean floor, embedded in images. A Puerto Rican in exile looking to the island and back again to the South Bronx and Spanish Harlem. All the work of the artists I knew then from Puerto Rico were wrapped up with being Puerto Rican and being a Puerto Rican in New York. It was about loss, separation, being apart. The gulf was enormous and yet in your face. It divided the island from the exiles and yet it also brought them together. Thus the outpouring of creative endeavours throughout that brief window of time, was incredible. For around twenty years, from the late 1960s to the beginning of the 1980s (when Reagan became prez actually and neoliberalism was unleashed), painting, sculpture, poetry, public art, music, photography, drama and politics of course, all exploded out of Nuevayork, a renaissance comparable to that of the Black Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and 30s. All of it powered by a yearning for independence, not only for the island but from gringo culture. The weird thing is that I found myself caught up in it, pure serendipity really. I was in the right place at the right time. I suppose it worked because I brought unique skills and experiences to bear, a different yet connected viewpoint. I was, after all, a second generation immigrant to the UK myself. I even had relatives in New York that I knew nothing about, who had fled Russia at the same time as my grandparents had (the last decades of the 19th century)! Apparently, my grandmother Etty had been on her way to New York to join them but got pregnant on the way and ended up in a ghetto in Leeds, Yorkshire instead, where my mother was born.

So, once more I’m asked to write an essay essentially on the same subject of the colony but more precisely the colony of the mind of how the culture of Puerto Rico has been colonised, coopted, included but yet excluded. How is this possible? Nestor, who sadly is no longer with us, I miss him terribly as do all those who knew him and loved him, would no doubt have something important to say on the subject but he was never bitter, never cynical, always positive, thus his take would have included his humour, that wry smile he always carried, that I’ll always remember him by.

Puerto Rican-Hispanic culture has, in its way, entered the mainstream of US life, largely through its monetization/emasculation and in doing so, it’s lost its immediacy and its connections to those, now far-off days, of make do and mend, the sense of community, of belonging that made it so powerful, so vibrant and alive. Its sense of purpose! And at the same time, a decaying US capitalism has immiserated the island of Puerto Rico even further, reduced it to a broken and corrupt land, now abandoned, unloved and uncared for and drifting rudderless in the Caribbean Sea by its US master, no longer of consequence for the making of cheap t-shirts or Disney bric-a-brac. The ignominious end to a colonial mission.

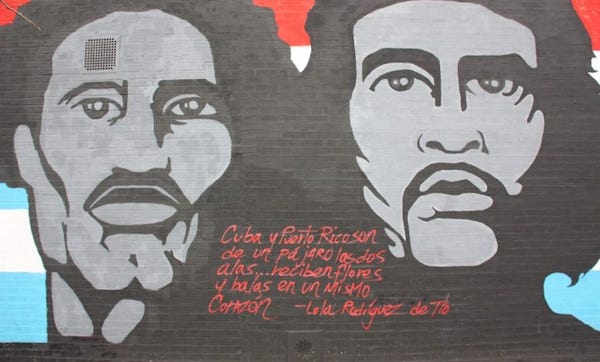

East Harlem defends ‘Dos Alas’ mural of Puerto Rican & Cuban solidarity

And what of Nuevayork? Well, currently going through the process of gentrification as with much of the working class communities trapped and surrounded by enclaves of wealth, which the fight over the mural personifies. The building on which it resides has new owners and the mural no longer belongs, like so much else that is/was Spanish Harlem. In reality, this is not only a fight over a mural but a fight over history and who it belongs to, about the desire for autonomy, about belonging, about identity, about liberation. It’s about all those creative minds that I mingled with 40 years ago, who had a dream, who connected, who created the realities that liberated the mind.

William Bowles, London, March, 2023

This is my first essay on Substack and I had a devil of a job actually publishing the damn thing! I'm still not sure if it's actually visible.